Escape calculator update illustrates pleiotropic constraints on SARS-CoV-2 RBD evolution

I've updated the SARS-CoV-2 RBD antibody escape calculator with new yeast-display deep mutational scanning data from Yunlong Cao's group. My interpretation: the antigenic evolution of the RBD is currently constrained by the pleiotropic effects of mutations on 1:1 RBD-ACE2 affinity, up-down RBD positioning in the context of full spike, and antibody neutralization.

Escape calculator update

The SARS-CoV-2 RBD escape calculator is an interactive tool that our lab developed several years ago to aggregate yeast-display deep mutational scanning data on how mutations affect binding of antibodies to the RBD. See the original paper for an overview of how it works. The current calculator shows data from a wonderful set of deep mutational scanning studies by the lab of Yunlong Cao (eg, Cao et al (2023), Yisimaya et al (2024), and Jian et al (2024)). The current update adds the deep mutational scanning data from the last of these papers (Jian et al (2024)), which incorporates antibodies from people with XBB or JN.1 lineage infections.

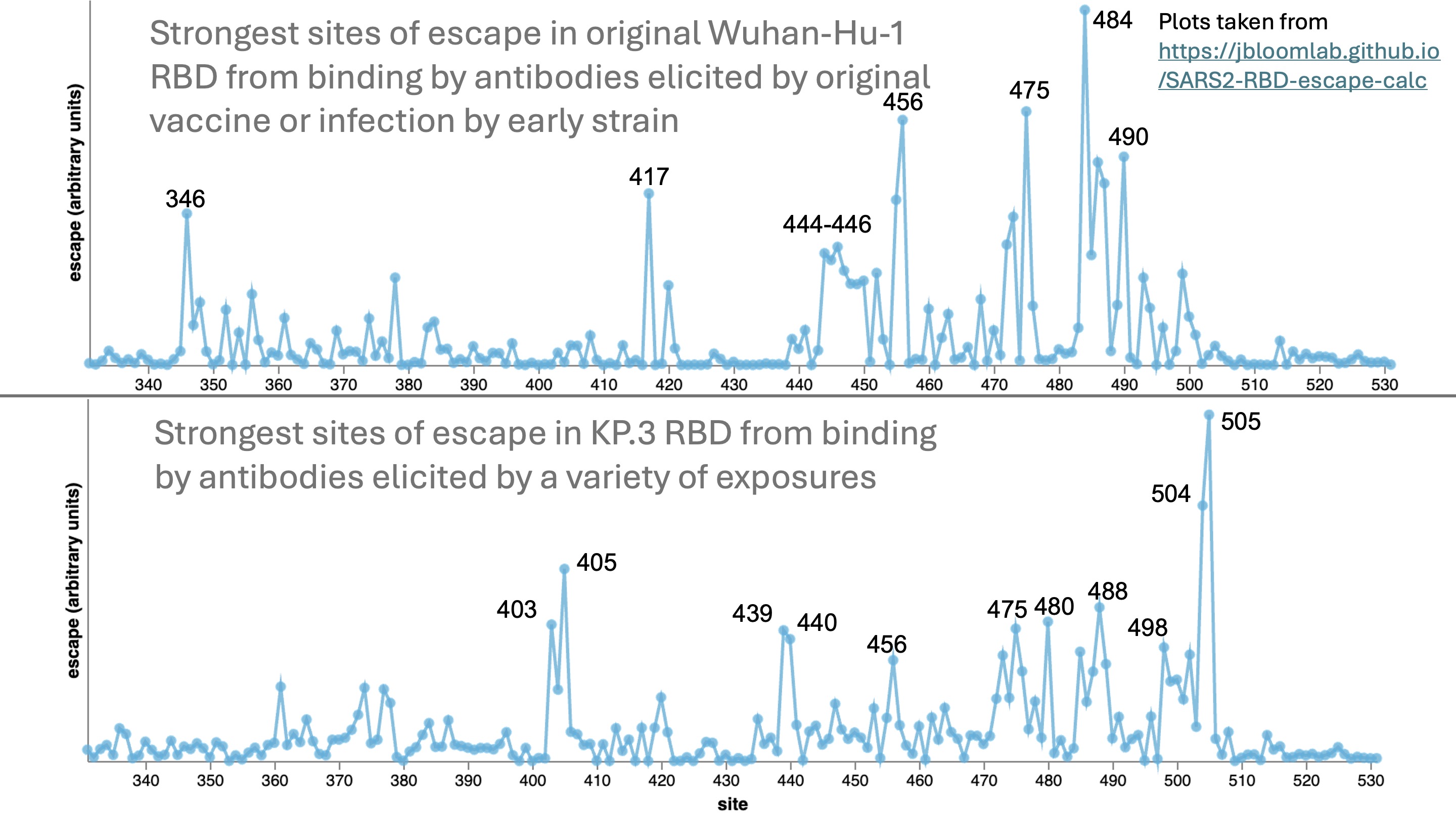

If you use the calculator to compare the sites of escape in the KP.3 variant from the current set of antibodies versus the original RBD from antibodies elicited by the ancestral vaccine, it is remarkable how much the antigenicity (key sites of escape) in the RBD have changed over the last four years:

Note that unlike the logo plots in the Cao lab papers, the escape calculator is not weighted by how mutations affect ACE2 binding or their amino-acid accessibility given the genetic code. So the calculator is designed to quantify the antigenic effect if a site is mutated, not predict how likely it is to mutate.

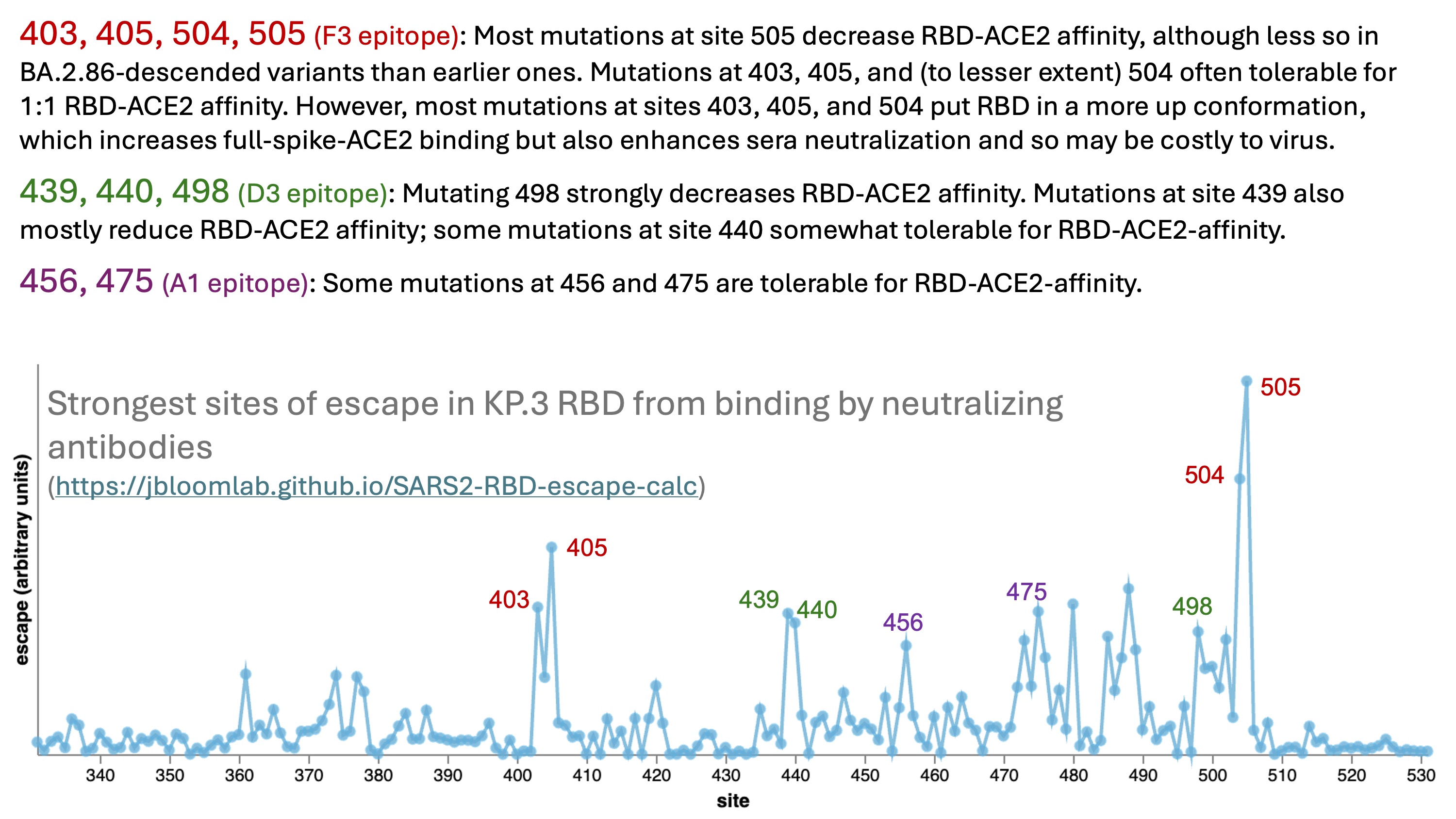

The strongest sites of escape from binding by neutralizing antibodies targeting the RBD are shown in the plot below, and fall in three different epitopes in the Cao lab nomenclature:

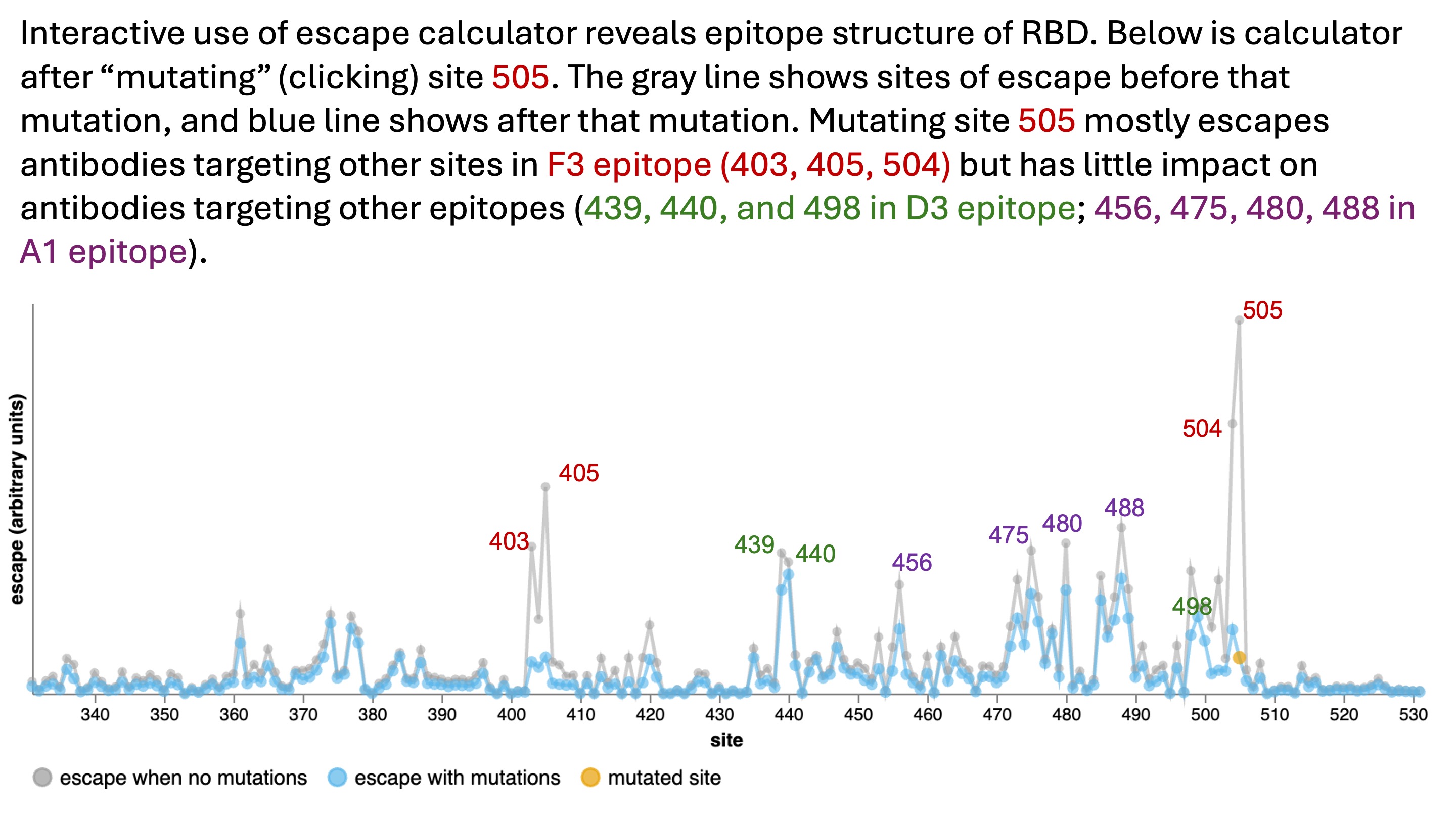

Note that while the escape calculator initially just looks like a line plot, its interactivity allows you to explore epitope relationships among sites. For instance, clicking site 505 to simulate mutating it also escapes most antibodies targeting sites 403, 405, and 504, since these sites are in the same epitope.

Why aren't we seeing more substitutions at sites 403, 405, 504, and 505 right now?

The updated escape calculator described above clearly shows that mutations in the epitope consisting of sites 403, 405, 504, and 505 cause a lot of escape from binding by neutralizing antibodies targeting the RBD. And mutations at sites 403, 405, and 504 (less so site 505) are often tolerable for the 1:1 RBD ACE2 affinity (see RBD yeast display data for ACE2 affinity recently published by Taylor and Starr (2024)). So why aren't these sites substituting more right now?

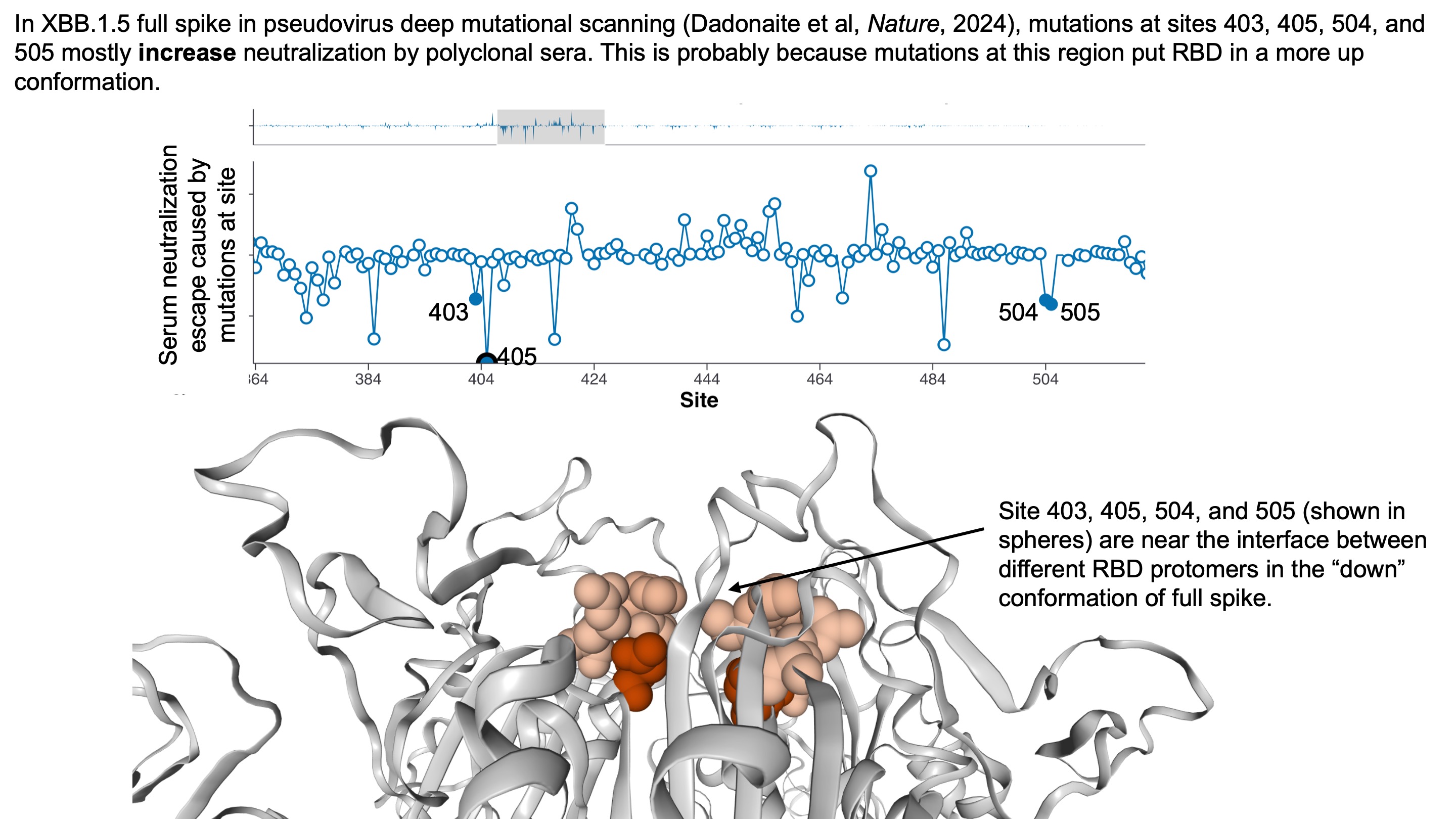

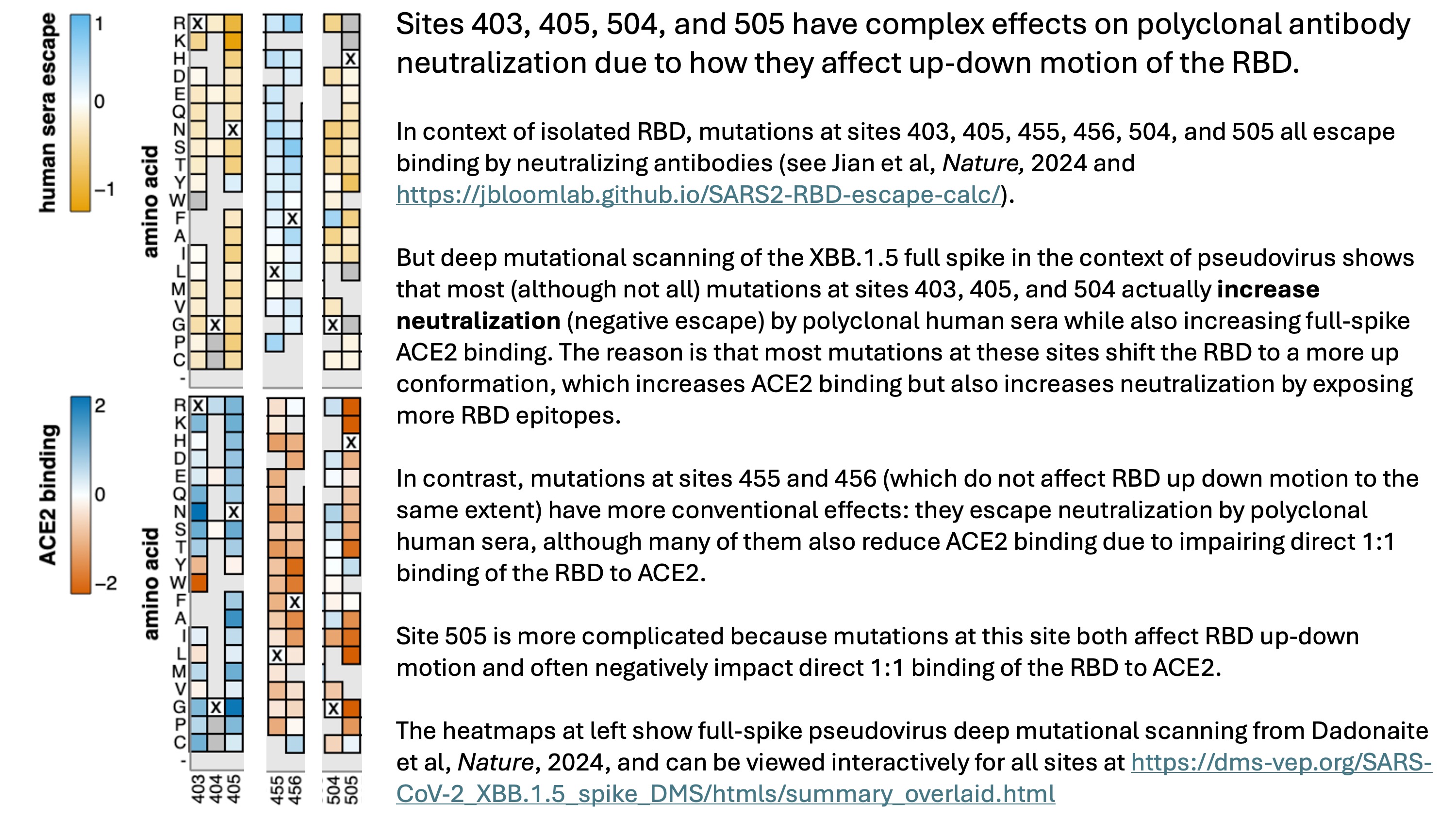

Answering this question requires thinking about the full spike, not just the RBD. Sites 403, 405, 504, and 505 are clustered near an inter-protomer interface in the down RBD structure. And most mutations at those sites actually increase neutralization by polyclonal sera in our lab's recent XBB.1.5 full-spike deep mutational scanning:

The data in our recent paper indicates that sites that modulate RBD up-down positioning are characterized by opposing effects on full-spike ACE2 binding and polyclonal serum neutralization. In particular, mutations that move the RBD more to an up conformation increase binding to ACE2 by the full spike (since the RBD is better poised to bind ACE2), but also increase serum neutralization since the RBD in the up conformation exposes more neutralizing epitopes. Importantly, these effects are not apparent in deep mutational scanning of just yeast-displayed RBD, since the RBD is outside the context of the full spike. If you look at our pseudovirus deep mutational scanning data (the full data can be interactively explored here), you can see that most mutations at sites 403, 405, and 504 increase full-spike serum antibody neutralization while also increasing full-spike ACE2 binding, suggesting the put the RBD in a more up conformation. (For site 505, it is more complicated because mutations at this site often also directly impair the direct 1:1 RBD-ACE2 binding, as can be seen here).

Therefore, evolution of the RBD is currently constrained by pleiotropic effects of mutations at key sites on antibody binding to RBD, RBD up-down motion, and 1:1 RBD-ACE2 affinity. That's probably why mutations at key escape sites like 403, 405, 504, and 505 have not yet swept.

Note that I expect evolution will eventually solve this pleiotropic puzzle through some epistatic combination of mutations--we’ve seen SARS-CoV-2 fix antibody escape mutations that were individually deleterious in the past. But for now, above observations may explain why recent variants (KP.3.1.1 & XEC) are mostly escaping neutralization via NTD mutations that put RBD more down (as described in recent work by David Ho and Shan-Lu Liu), rather than by direct antibody-escape mutations in the RBD as was common until recently.

Data underlying this post

For the data underlying this post, see:

- Escape calculator w how mutations affect RBD binding by neutralizing antibodies: https://jbloomlab.github.io/SARS2-RBD-escape-calc

- Data from @tylernstarr on how mutations affect 1:1 RBD-ACE2 affinity: https://tstarrlab.github.io/SARS-CoV-2-RBD_DMS_Omicron-EG5-FLip-BA286/RBD-heatmaps/

- Data on how mutations affect full-spike neutralization and ACE2-binding: https://dms-vep.org/SARS-CoV-2_XBB.1.5_spike_DMS/htmls/summary_overlaid.html